Plants, Robots, and Other Interesting Things

A UArizona doctoral student relies upon CyVerse to discover how plants grow in different environmental conditions.

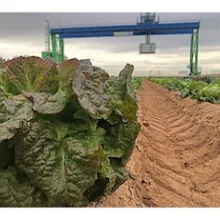

The Field Scanner at the Maricopa Agricultural Center is the world's largest agricultural robot.

Emmanuel Gonzalez has been exploring nature since early childhood in El Centro, California. He recalls staring up at the stars and planets with a beginner's telescope at a young age. After developing an interest in plant science during an internship at the Boyce Thompson Institute, he earned his Bachelor of Science in general biology at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, Washington, and is now a doctoral student in UArizona's School of Plant Sciences in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

He works under assistant professor Duke Pauli, but says he's been "adopted by Eric's lab." He's talking about Eric Lyons, CyVerse co-principal investigator and associate professor of plant sciences.

Pauli and Lyons and their teams work together on UArizona's Department of Energy-funded Field Scanner, the world's largest agricultural robot. This unique system is capable of collecting images of crops, and measurements derived from those images, as well as environmental measurements from several sensors.

Emmanuel Gonzalez

"My main responsibilities with the Field Scanner include writing codes, validating the codes the team writes, and coordinating all the graduate students' activities," Gonzalez said.

"It has been absolutely stunning to watch Emmanuel, as well as the entire team of students, develop such a remarkable skill set in such a short amount of time to support such a significant and unique project – our group meetings are easily the highlight of the week!" said Pauli. "I am always impressed by how much progress they make."

The team writes a variety of codes to process the data collected by the Field Scanner. The majority are pre-processing codes, which convert data files from one format to another, but the team also needs codes to perform myriad other functions, such as clipping images of agricultural plots, integrating machine learning algorithms to identify every plant in the field, and extracting information such as plant size and photosensitivity. In addition, there is a major challenge in the amount of data that needs to be processed, often exceeding 100 Terabytes for a single 3-month growing season.

"The goal is to provide computational tools not only for our project, but that also can be leveraged by other scientists – this is something we always try to keep in mind," Gonzalez said.

The analyses are used to create computational models that link environmental, genetic, and phenotypic data of the study plants. "With this much data, we're uniquely situated to try to model that information," Gonzalez said. "That is the focus of my dissertation."

To perform these analyses, Gonzalez said: "I use CyVerse a lot."

"CyVerse spans every aspect of our data processing," he explained, "allowing us to transfer our data from one computational environment to the next."

"We store our raw data in the CyVerse Data Store, download it from CyVerse onto the UArizona high-performance computer where we can run our analyses, and compress the outputs and send the results back to CyVerse."

The raw data generated by the Field Scanner is between 2–10 Terabytes per day, transferred to the CyVerse Data Store using iRODS, the integrated Rule Oriented Data System, an open-source data management software.

"I think as science continues to generate more and more data, researchers are really going to benefit from these systems," Gonzalez said. "It's very simple and often overlooked, but very powerful. CyVerse makes these resources available to researchers at any stage of the data cycle."

"CyVerse also provides a network," he added. "We are one of many projects that leverage CyVerse. The ability to collaborate within CyVerse is extremely beneficial. The community helps us through problems that inevitably arise when dealing with such large datasets."

Gonzalez gets away from the computer in the summer. "When thinking about 'Big

Data,' a lot of people think you just collect the data and that's it," he observed. "We have to go into the field and hand-weed so that the plants we're imaging are the ones we want to study."

The team has investigated lettuce and sorghum, and will soon be looking at other crops. "We want to understand the dynamics of growth for various crops in response to changing environmental conditions that will reflect future climate scenarios," Gonzalez explained.

"Having students such as Emmanuel is an absolute pleasure. In one sentence, he can be talking about how to optimally organize plants and plots for planting, offer insights on how to make engineering changes to the scanning hardware, and discuss novel machine learning methods for identifying traits and features of plants," said Lyons. "He represents a new kind of scientist who can become expert in many disciplines and technologies, easily spanning life science and computer science."

Gonzalez still explores nature. At work, he uses the lens of science. Otherwise, he uses his camera lens. His images of wildlife, plants, mushrooms, lichens – and explanations of each organism's role in the environment – can be found on Instagram at curious.student.botanist.

Gonzalez likes to share the skills he's developed with others through mentoring students. "To the young scientists out there," he said, "always keep an open, curious mind. That initial curiosity you have today will take you down interesting paths."

Gonzalez's PhD will be in plant sciences, but he would like to go into computational biology, a field for which his current work imminently prepares him. "Science is rarely one thing," he said. "You may go in to study one thing, but in the process, you end up working with all these other interesting things."

Photos courtesy of Emmanuel Gonzalez/UArizona.