Revealing Wild Cats

A wildlife monitoring project securely shares data about endangered cats.

Courtesy Charles J. Sharp. CC BY–SA 4.0

One night in November 2012, a wildlife monitoring camera captured an image of a jaguar traveling through the Santa Rita mountains south of Tucson, Arizona. Black spots dappled his tawny coat as he padded through the nighttime forest.

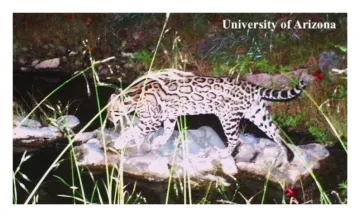

Night Patrol: An endangered male jaguar detected in the U.S. thanks to the Wild Cat Conservation Project. Courtesy University of Arizona.

An adult male, he appeared to be in good health. He was also the only known jaguar in the United States at the time. The camera that snapped him was part of the Jaguar Survey and Monitoring Project in the United States led by the University of Arizona (UA). Without it, it’s likely no one would have known he was there.

Jaguars were believed to have been eliminated in the US in the 1960s. And while a few isolated sightings cropped up around the turn of the millennium, they remain an elusive and endangered species.

Getting an accurate count of how many of these wild cats are currently living in the US-Mexico Borderlands is needed to monitor population health and identify travel corridors for conservation.

Since the detection of the Santa Rita jaguar, the Wild Cat Conservation Project has identified three more jaguars inhabiting various mountain ranges on the US side of the border—and even more ocelots. Overall, the project has monitored more than 50 different species, including eight threatened and endangered species.

“It’s a fantastic survey of wildlife across the Borderlands,” says Susan Malusa of UA’s Wild Cat Research and Conservation Center. “Not only jaguars and ocelots, but all the wildlife in these areas.”

Tracking a wild cat

Because the survey deals with endangered species, only passive monitoring and other non-invasive methods are used. Since 2012, the project has placed motion-activated cameras at more than 300 sites across ten mountain ranges in the Borderlands.

The camera doesn't discriminate: While the aim of the project is monitoring endangered species such as jaguars and ocelots, the 300 camera sites also detect other wildlife such as pumas, bobcats, bears, deer, coatis, tortoises, and Gila monsters. Courtesy University of Arizona.

To access so many sites in remote areas, the project enlists the help of citizen scientists. These volunteers receive several days of intensive training covering spotted cat ecology, tracking, safety, GPS and other equipment use, species ID, camera trap functionality, and downloading and sorting data.

“They are fantastic,” says Malusa. “The first nine citizen scientists started in 2013, and now we have thirty-five, and a list of fourteen more are waiting to be trained soon.”

“It’s a fun project for volunteers, whether they want to hike or help with sorting wildlife images, there is something for everyone,” she adds. “We’ve been asked to bring the project to youth in the schools, and we would love to do this, but we don’t have the resources at this point in time.”

Each trained citizen scientist has their own route. They travel to their assigned sites and make sure the camera is still functional, put in fresh batteries, collect SD cards and put in new ones, and take a few test photos to make sure the camera is still in position.

But the project’s expansion over the years has meant a corresponding expansion of data. It soon became more than the core team could handle locally. That’s when they turned to CyVerse, an organization that provides computational infrastructure for life scientists.

Curiosity killed the camera: Bears and coyotes sometimes destroy the remote cameras in an attempt to figure out what they are. Courtesy University of Arizona.

“Our citizen scientists used to have to process the data through multiple steps at home and then put it on a hard drive and physically deliver it to the UA campus,” says Malusa. “Our goal was to create a platform where they could upload and share data, and where we can also collaborate with other people doing projects like ours.”

But they encountered some bumps along the way. One of the first steps in the CyVerse collaboration was to move seven million images (nearly 10 terabytes of data) from a Windows server in the ecology building on the UA campus to a more centralized location.

“When you move 10,000 images that are really small and are sending them over the network, the network doesn’t like that. It prefers large files,” says Blake Joyce, assistant director of research computing at UA.

“You have to figure out how to bundle everything up and send it over and make sure you haven’t lost anything,” Blake adds. “When you have seven million images, you’re not just going to eyeball it and say, ‘Yeah, you missed a coati in there.’”

The resulting SPARC’d (Scientific Photo Analyses for Research and Conservation database) collects the projects geotagged image data in a central location and makes it available for analysis. Researchers can look at species distance to water, vegetation, and preferred movement patterns across the landscape (travel corridors), all of which inform conservation and management decisions.

“With our system, we can set up collection permissions and share data with scientists or with agencies needing data to help inform conservation and management decisions,” says Malusa.

Keeping a secret: Working with endangered species means archived data needs to be secure. Courtesy University of Arizona.

Because of its security and ease of use, researchers around the globe can contribute their own data. For example, a scientist in Namibia is using the application to upload and analyze his data about the caracal, or desert lynx.

“Working with CyVerse has been critical to our success and our ability to assure collaborators that the system is secure,” says Malusa. “We have sensitive data and the system allows us to use the security built into CyVerse.”

The next step will be to speed up the process of sorting and analyzing captured images using augmented intelligence. So far the team has been successful in a test using machine learning to eliminate ghost images. (Up to 90 percent of images captured are the result of the camera being activated by a branch swaying in the wind). This will ultimately save time over each image having to be verified by a human researcher.

“Cats are pretty quiet creatures. So maybe it’s crouched in the grass and it’s really hard to see, so the machines don’t pick it up,” says Malusa. “Humans are pretty good at that sort of pattern recognition.

“But the more steps there are, the greater the chance of an error. AI will help eliminate repetitive tasks like sorting images and instead allow humans to spend their time on species analysis and field work.”

Evaluating impacts: Long-term collection of geotagged data could help accurately assess the impact of construction projects on surrounding habitats. Courtesy University of Arizona.

Sharing the neighborhood

The researchers never lose sight of why they’ve undertaken this work in the first place—to preserve endangered wildlife. The project’s extended dataset lets researchers look at changes to wild cat habitat, such as where water is available and where perennial water sites may have disappeared, perhaps due to climate change.

The collected geotagged species data could also help with planning construction projects. For example, if a company applied to the state for a permit to build a mine in a certain mountain range, the project database could quickly supply exact information on which endangered species are living near the proposed site, allowing potential impacts to be more accurately evaluated.

Tracking big cats and safely sharing data about their presence is sure to benefit both humans and their wild neighbors. The more we learn about the species with whom we share our surroundings, the better we can appreciate and protect them.