Data on Demand: Creating a Search Engine for Microbiome Sciences

The Hurwitz Lab makes extremely large data sets from a range of storage servers searchable to assist scientific discovery.

Scientists working on the Hawaii Ocean Time-series and Bermuda Atlantic Time-series programs have been making repeated observations of the physical, biological and chemical properties of the ocean since 1988. Now, thanks to the Hurwitz Lab at the University of Arizona, researchers around the world have greater access than ever before to the information collected at the remote ocean sites.

Bonnie Hurwitz next to the metal pod that serves as the main chamber for the Alvin submersible that scientists operate to collect samples from the deepest parts of the ocean not accessible to people. Photo taken at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. (Photo: Stefan Sievert)

Led by Bonnie Hurwitz, assistant professor of biosystems engineering in the UA College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, the Hurwitz Lab corrals big data sets into a more searchable form to help scientists study microorganisms – bacteria, fungi, algae, viruses, protozoa – and how they relate to each other, their hosts and the environment.

The lab is building a data infrastructure on top of CyVerse, also led by the UA, to integrate and build information from diverse data stores in collaboration with the broader cyber community. The goal is to give people the ability to use data sets that span a range of storage servers, all in one place.

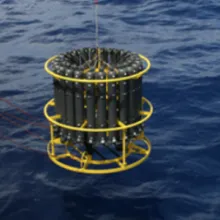

"One of the exciting things my lab is funded for is Planet Microbe, a three-year project through the National Science Foundation, to bring together genomic and environmental data sets coming from ocean research cruises," Hurwitz said. "Samples of water are taken using an instrument called a CTD that measures salinity, temperature, depth, and other features to create a scan of ocean conditions across the water column."

As the CTD descends into the deep dark ocean, bottles are triggered at different depths to collect water samples for a variety of experiments including sequencing the DNA/RNA of microbes. The moment each sample leaves the ship is often the last time these valuable and varied data appear together.

The first phase of the project focuses on the Hawaiian Ocean Time Series and the

A CTD device that measures water conductivity (salinity), temperature and depth is mounted underneath a set of water bottles used for collectiong samples at varying depths. (Photo: Tara Clemente, University of Hawaii)

Bermuda Atlantic Time Series. At both locations, samples are collected across an ocean transect at a variety of depths across the water column, from surface to deep ocean.

The readings taken at each level stream out to different data banks around the world. Different labs conduct the analyses, but the Hurwitz lab reunites all of the data sets from the project, including data from these long-term ecological sites used for monitoring climate and changes in the oceans.

"Oceanographers have different tool kits. They are collecting data on ship to observe both the ocean environment and the genetics of microbes to understand the role they play in the ocean," Hurwitz said. "We are including these data in a very simple web-based platform where users can run their own analyses and data pipelines to use the data in new ways."

Hurwitz and Amy Apprill, associate scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Instititution, in front of the human-piloted Alvin submersible. Deep-water samples are collected using the pod's robotic arm becasue the pressure of the water is too Intense for divers.(Photo: Stefan Sievert, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

While still in year one of the project, the first data have just been released under the Hurwitz Lab's iMicrobe platform. This integrated platform provides users with interactive visualizations they can mine and convert to knowledge nd information to drive science.

The purpose is not just to access that data itself but also to connect users with computational resources for analyzing the data. It's possible to use modern bioinformatics tools on this platform to analyze the data in new ways that may not have originally been possible when the data were collected, or to compare these global ocean data sets with new data as it becomes available.

"We're plumbers, actually, creating the pipelines between the world's oceanographic data sets. We're trying to enable scientists to access data from the world's oceans," Hurwitz said.

A larger mission

In addition to their Planet Microbe work, Hurwitz and her team work with the three entities that store and sync all of the world's "comics" (genomics, proteomics) data – the European Bioinformatics Institute, the National Center for Biotechnology Information and the DNA Databank of Japan. The lab is also working with the Joint Genome Institute with the Department of Energy, the Human Microbiome Project, and others.

"We are working with the National Microbiome Collaborative, a national effort to bring together the world's data in the micro biome sciences, from human to ocean and everything in between," Hurwitz said, adding that her research team generally includes UA students who benefit from the global experience.

"Having those data sets captured and searchable is great," said Hurwitz, who is a member of the UA BIO5 Institute. "They are so big they can't be housed in any one place. The infrastructure allows you to search across these areas. If we want to start looking at things together in a holistic manner, we need to be able to remotely access data that are not on our servers. We are essentially indexing the world's data and becoming a search engine for micro biome sciences."

By reconnecting 'omics data with environmental data from oceanographic cruises, Hurwitz and her team are speeding up discoveries into environmental changes affecting marine microbes that are responsible for producing half the air that we breathe. These data can be used in the future to predict how our oceans respond to change and to specific environmental conditions.

The Hurwitz Lab also holds another grant from the National Science Foundation: the Ocean Cloud Commons. For that project, they are creating a computer framework for the ocean sciences that allows scientists to compare massive genomic data sets from the ocean.

"Our researchers can not only use a $30 million supercomputer at XSEDE (Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment) supported by the National Science Foundation for running analyses, they also have access to modern big data architectures through a simple computer interface."

The Hurwitz Lab also conducts outreach education at Tucson High and Basis schools in Tucson and Scottsdale Preparatory Academy in Phoenix to give high school students the knowledge to use these data sets while learning computer science skills to go deeper.

"We're trying to understand where all the data are and how we can sync them," Hurwitz said. "How data are structured and assembled together has been like the Wild West. We're figuring it out."